How much Wine are Canadians drinking? 5 Interesting Insights

Wine consumption patterns across Canada reveal fascinating insights about regional preferences, economic trends, and cultural influences. This comprehensive analysis examines two decades of wine consumption data to uncover the surprising realities behind what, where, and how Canadians enjoy their wine, providing a window into the nation’s evolving relationship with this popular beverage.

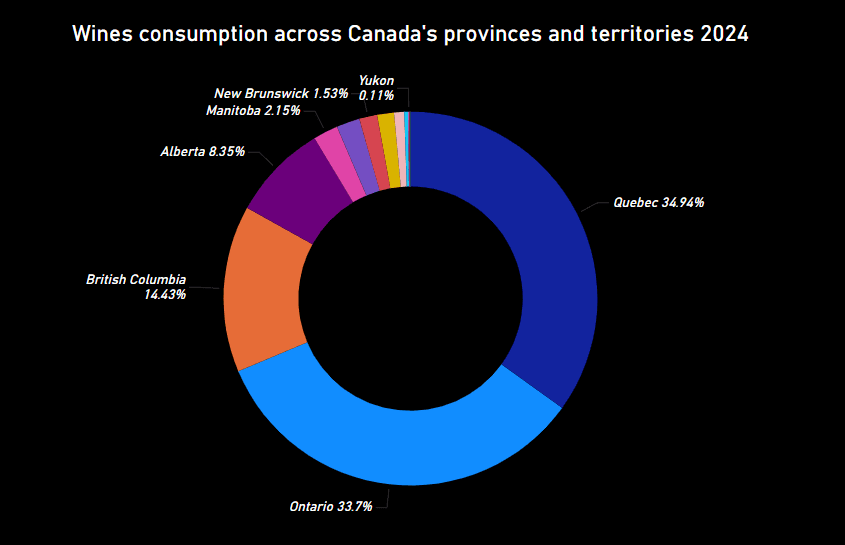

Beyond Quebec’s Reputation: Who’s Actually Drinking the Most Wine?

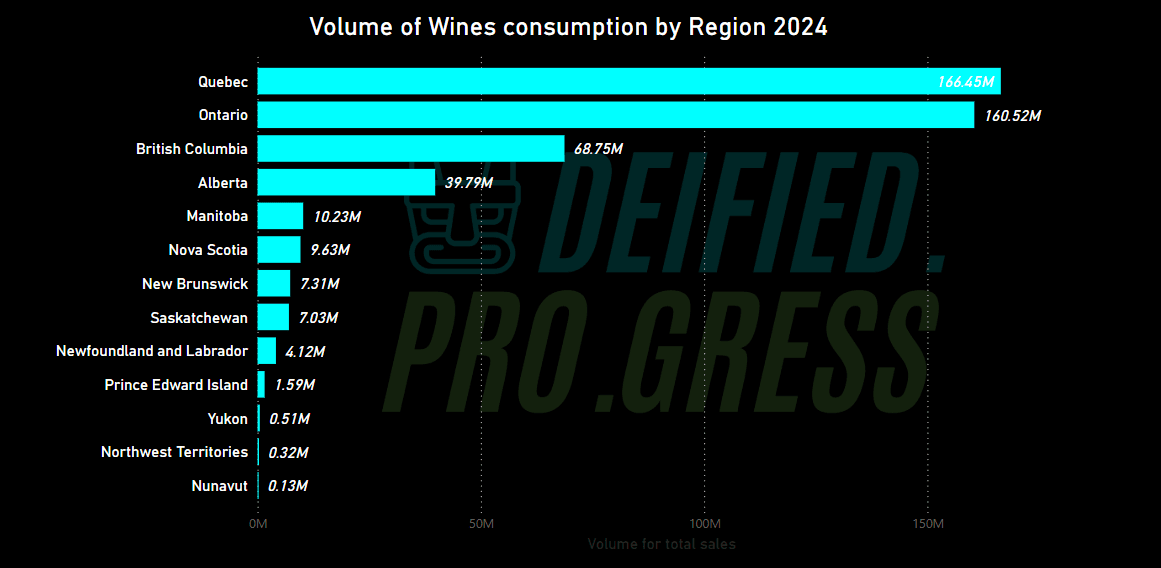

Quebec stands as the undisputed leader in Canada’s wine consumption landscape, accounting for 34.94% of the country’s total wine consumption according to the 2024 data. Ontario follows closely at 33.7%, meaning these two provinces alone represent nearly 70% of all wine consumed in Canada. British Columbia claims a respectable 14.43% share, while Alberta contributes 8.35%. The remaining provinces and territories collectively account for less than 10% of the nation’s wine consumption.

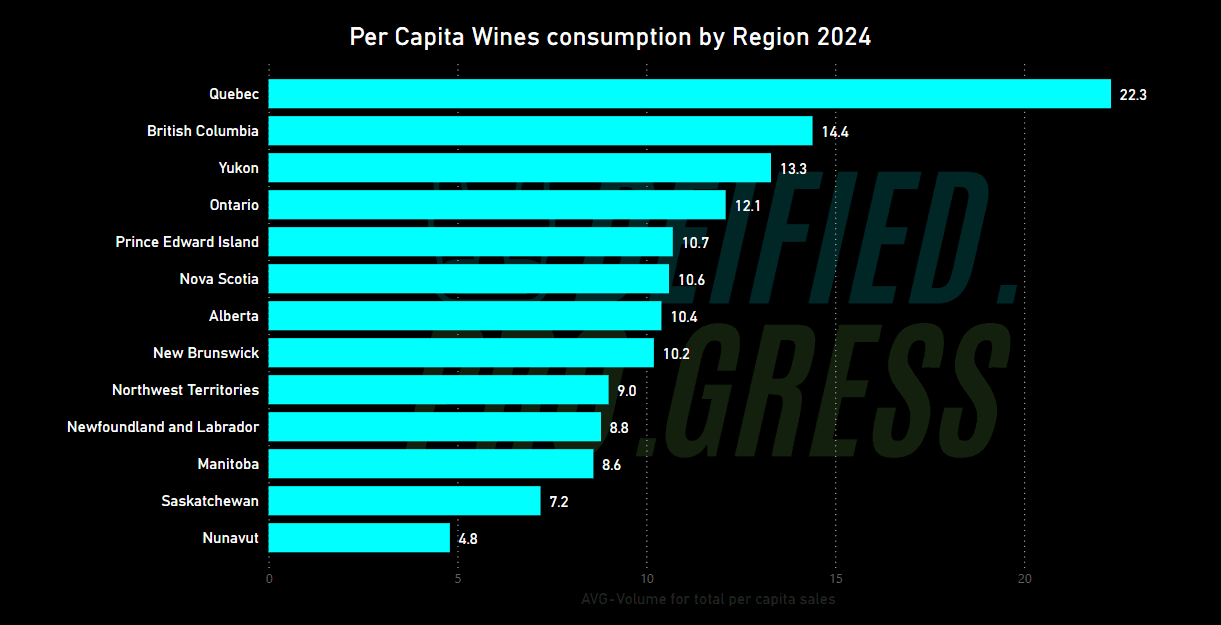

However, the per capita consumption data tells a substantially different story about Canadian wine culture. When examining consumption on an individual basis, Quebec still maintains its dominant position with an impressive 22.3 liters per person annually – nearly twice the national average. This figure is particularly remarkable when compared internationally, placing Quebecers’ consumption habits closer to traditional wine-producing European countries than to their North American neighbors.

British Columbia emerges as the surprising second-place contender with 14.4 liters per capita, significantly outpacing Ontario’s 12.1 liters despite having a much smaller population base. This suggests that wine has become deeply integrated into British Columbian culture, possibly influenced by the province’s thriving domestic wine industry centered in the Okanagan Valley.

Perhaps most unexpected is Yukon’s strong showing at 13.3 liters per capita, ranking third nationally despite representing a mere 0.11% of total consumption. This northern territory’s impressive consumption rate may reflect several factors: higher disposable income, a demographic profile skewed toward wine-consuming age groups, limited entertainment options in remote areas, or possibly the influence of tourism.

Prince Edward Island (10.7 liters) and Nova Scotia (10.6 liters) round out the top five per capita consumers, demonstrating Atlantic Canada’s growing wine appreciation. In contrast, the Prairie provinces show more modest consumption levels, with Saskatchewan (7.2 liters) and Manitoba (8.6 liters) ranking among the lowest mainland provinces. Nunavut reports the lowest consumption at 4.8 liters per person, likely reflecting a combination of demographics, accessibility challenges, and cultural preferences.

These regional disparities highlight how wine consumption transcends mere population distribution to reveal deeper cultural, economic, and geographic influences across Canada’s diverse landscape. Quebec’s French heritage provides an obvious connection to wine culture, but the strong showing from British Columbia and Yukon suggests that other factors – including local wine production, tourism, demographic composition, and economic prosperity – play significant roles in shaping provincial wine preferences.

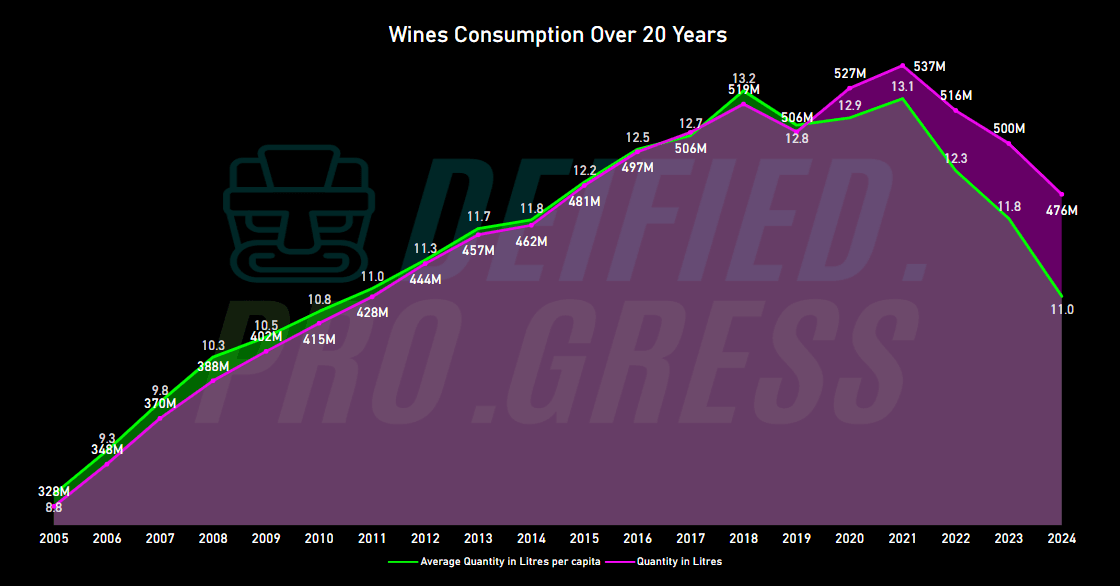

Why Are Canadians Drinking Less Wine Now Than Five Years Ago?

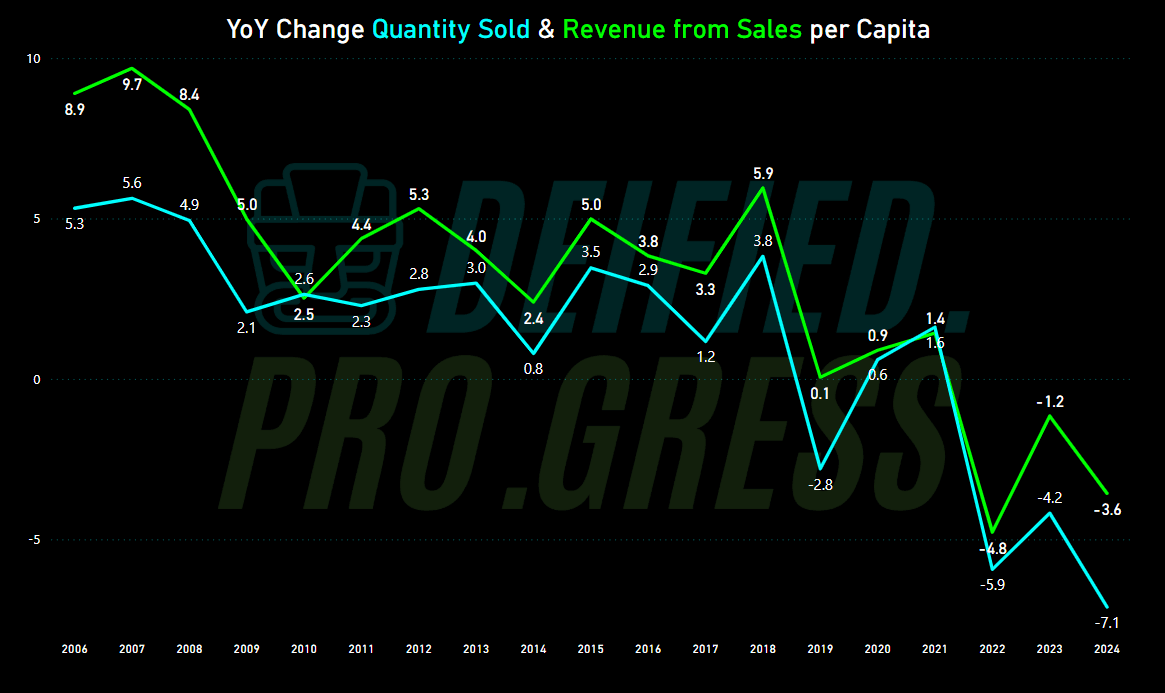

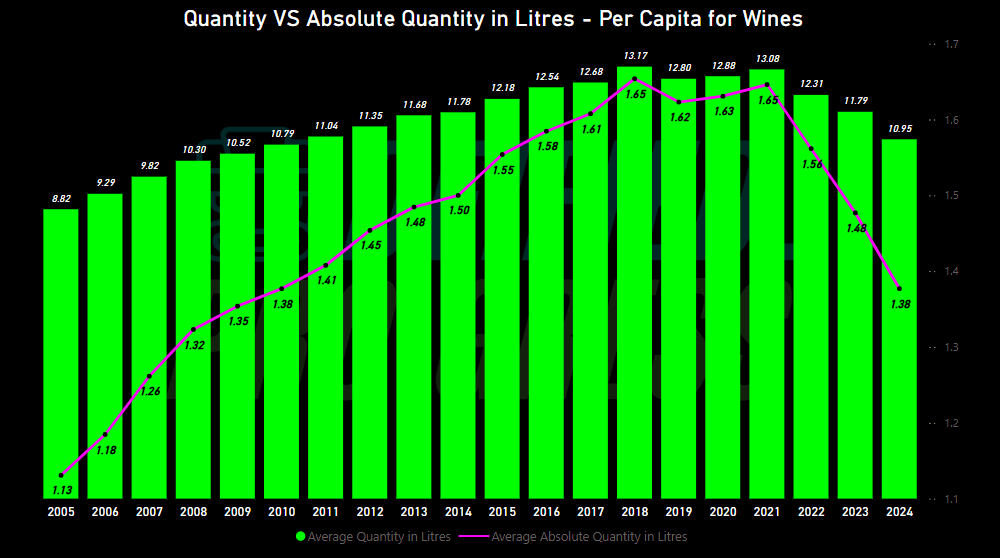

After steady growth from 2005 to 2019, when per capita consumption increased from 8.8 liters to a peak of 13.2 liters, Canada has experienced a surprising reversal. The data shows a clear downward trend beginning in 2018, with consumption dropping to just 11.0 liters per person by 2024 – levels not seen since 2015.

This decline isn’t merely a pandemic blip. The year-over-year data reveals negative growth continuing through 2022 (-5.9%) and accelerating in 2024 (-7.1%). This represents the most sustained decline in the entire 20-year dataset. Several factors may explain this trend:

- Health and Wellness Movement: The decline coincides with growing health consciousness among Canadians, particularly younger consumers who are increasingly mindful of alcohol’s health implications. The rise of “sober curious” movements and low/no-alcohol alternatives suggests a broader societal shift toward moderation.

- Changing Demographics: Canada’s aging population combined with different consumption patterns among younger generations is reshaping the market. Millennials and Gen Z demonstrate different alcohol preferences than their predecessors, often favoring spirits, ready-to-drink beverages, or abstaining altogether.

- Economic Pressures: The post-pandemic period has seen significant cost-of-living increases and economic uncertainty. Wine, particularly at mid to higher price points, may represent a discretionary expense that consumers have reduced during financial constraints.

- Competition from Alternative Beverages: The explosive growth of premium spirits, craft beer, seltzers, and non-alcoholic options has created unprecedented competition for consumer attention and spending. The RTD (ready-to-drink) category, in particular, has captured market share from traditional wine.

- Shifting Social Contexts: The pandemic fundamentally altered social gathering patterns and dining behaviors. With fewer restaurant meals and formal gatherings, occasions traditionally associated with wine consumption have diminished.

Do Higher Prices Mean Better Taste? The Provinces Paying Premium vs. Those Buying Volume

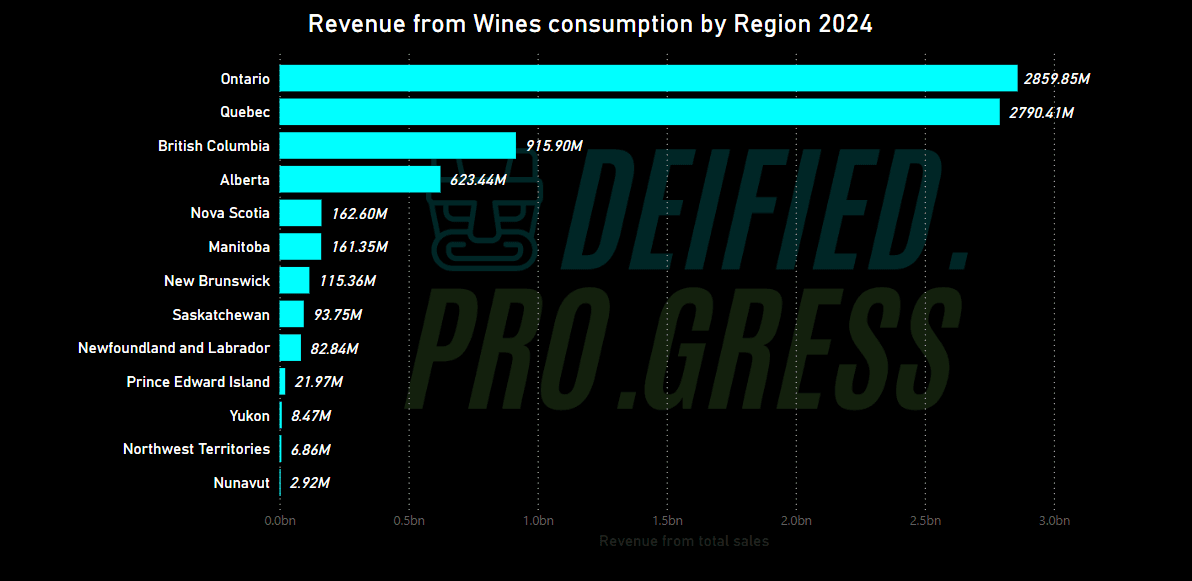

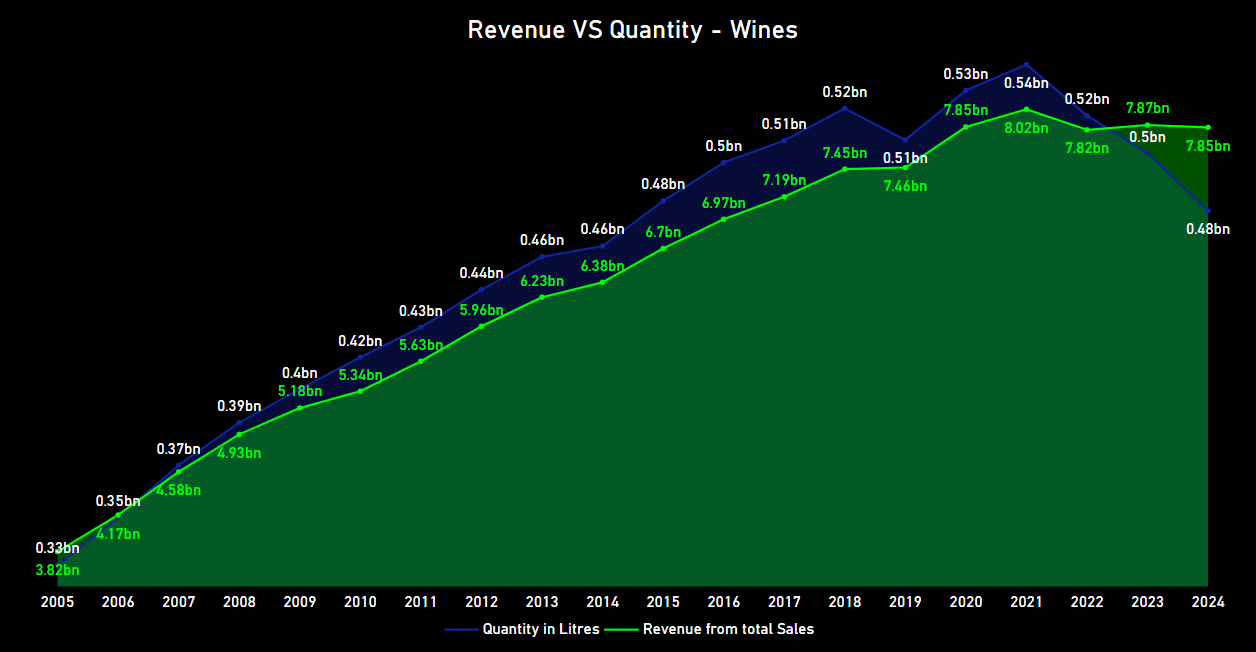

While Quebec leads in volume at 166.45 million liters compared to Ontario’s 160.52 million, Ontario generates more revenue at $2.86 billion versus Quebec’s $2.79 billion. This revenue-volume disparity points to Ontarians paying premium prices for their wines.

The data shows significant price variation across provinces:

- Ontario: $17.80 per liter average

- Alberta: $15.67 per liter average

- Quebec: $16.97 per liter average

Ontario’s premium pricing suggests a market oriented toward higher-end wines, with consumers willing to spend more per bottle. This could reflect the province’s restaurant culture, higher disposable income in urban centers like Toronto, or the success of LCBO’s premium wine marketing strategies. Quebec’s slightly lower per-liter cost, despite its higher consumption, may indicate greater access to affordable imported wines through its SAQ system or possibly higher volume purchases of moderately priced wines.

British Columbia presents perhaps the most intriguing case study in this analysis. Despite ranking third in both volume (68.75 million liters) and revenue ($915.90 million), its per-liter price of $13.32 is substantially lower than other major provinces – nearly 25% less than Ontario’s average.

The long-term trend also reveals that while both volume and revenue grew in parallel from 2005-2018, revenue growth has consistently outpaced volume growth, reflecting premiumization across the Canadian market.

How Did COVID-19 Change Canadian Wine Habits Forever?

The pandemic represents the most significant inflection point in Canadian wine consumption patterns. The data shows:

- Total consumption volume peaked in 2018 at 533 million liters

- By 2024, volume had fallen to 476 million liters (a 10.7% decrease)

- All major provinces show negative growth since 2020

The provincial breakdown reveals interesting variations in pandemic response:

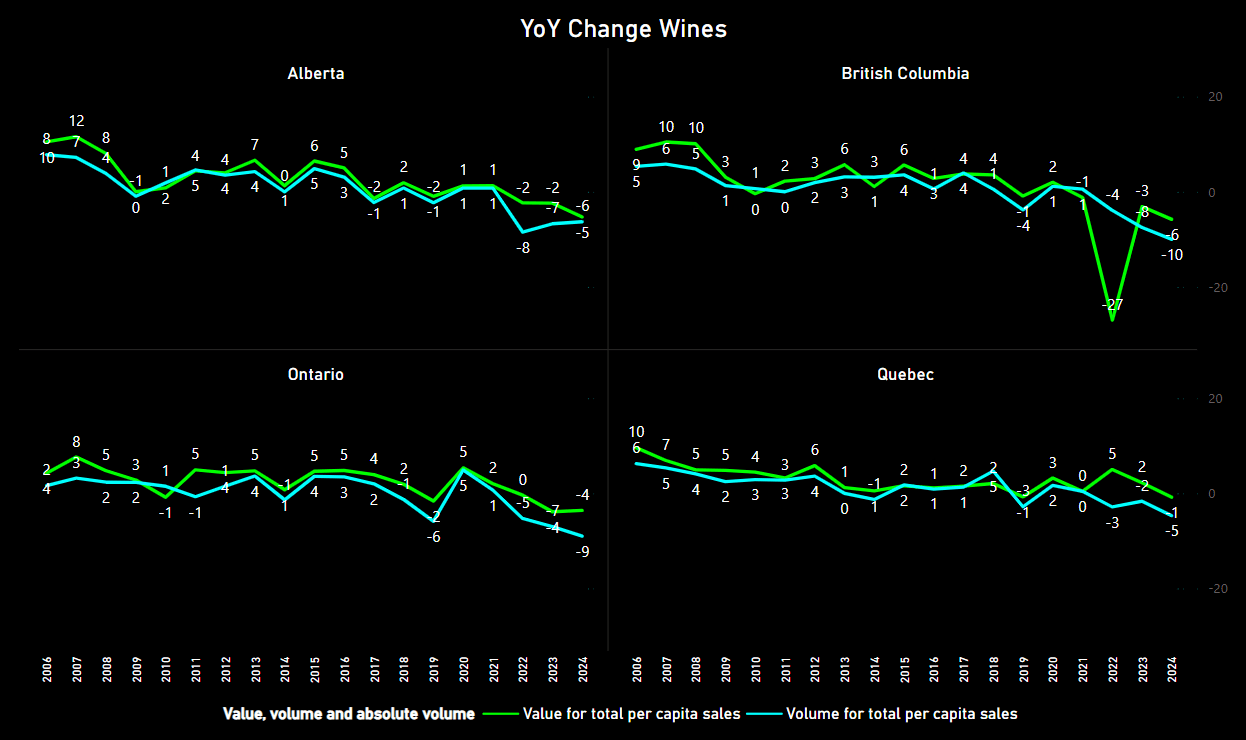

- British Columbia experienced the most dramatic decline, with a severe -27% drop in 2022

- Ontario showed the most resilience, with smaller declines and occasional positive growth years

- Alberta and Quebec both show consistent negative trends post-2020

These patterns suggest permanent changes in consumer behavior rather than temporary disruptions. Home consumption hasn’t fully replaced on-premise consumption lost during lockdowns, and new habits formed during this period appear to be sticking.

The provincial breakdown reveals fascinating variations in pandemic response and recovery:

British Columbia experienced the most dramatic decline, with a severe -27% drop in 2022 followed by continued negative growth. This suggests particular vulnerability in BC’s wine market, possibly due to its reliance on tourism, restaurant dining, and its local wine industry – all severely impacted by pandemic restrictions. The province’s stronger pre-pandemic growth makes this reversal especially striking.

Ontario demonstrated the most resilience among major provinces, with smaller declines and occasional positive growth years interspersed with the overall downward trend. This relative stability might reflect Ontario’s robust retail system, successful pivoting to e-commerce by the LCBO, or possibly stronger consumer finances in Canada’s largest provincial economy.

Alberta and Quebec both show consistent negative trends post-2020, though neither experienced the extreme volatility seen in British Columbia. Quebec’s decline is particularly notable given its traditionally strong wine culture and high per capita consumption.

Several factors appear to be driving these persistent changes:

- Channel Disruption: The pandemic fundamentally altered where wine is consumed. Restaurant and on-premise sales, which typically account for 20-30% of total wine consumption and skew toward higher price points, have not fully recovered to pre-pandemic levels. Home consumption hasn’t completely compensated for this shift.

- Acceleration of Existing Trends: The pandemic appears to have accelerated wine consumption declines that were already beginning to emerge in some demographics, particularly among younger consumers who were already shifting toward spirits, RTDs, or reducing alcohol intake.

- New Consumption Occasions: The pandemic normalized different drinking occasions – virtual gatherings, weeknight consumption, and at-home entertaining – which appear to favor different beverage categories than traditional restaurant and formal social occasions that typically featured wine.

- E-commerce and Direct-to-Consumer Growth: While online wine sales grew dramatically during pandemic restrictions, this channel shift appears to have benefited certain wine categories and price points differently, potentially reshaping overall consumption patterns.

- Economic Uncertainty: The economic volatility of the pandemic period, followed by inflation and cost-of-living concerns, has likely impacted discretionary spending on products like wine, particularly at premium price points.

The data strongly suggests these changes represent permanent shifts rather than temporary disruptions. The persistence of negative growth through 2023 and 2024, years after pandemic restrictions were lifted, indicates new consumer patterns have solidified. Home consumption patterns established during lockdowns haven’t fully replaced the on-premise consumption lost during this period, suggesting a fundamental reassessment of wine’s role in Canadian social and consumption habits.

This transformation of Canada’s wine landscape represents both challenges and opportunities for the industry. While overall consumption has contracted, the data shows less dramatic declines in revenue than in volume, suggesting consumers may be focusing on quality over quantity – a potential bright spot for premium wine producers even in a shrinking overall market.

Which Province Will Lead Canada’s Wine Market in 2030?

Projecting forward based on current trends, the future landscape of Canadian wine consumption could undergo significant reshaping by 2030. The data suggests several potential trajectories that could fundamentally alter the provincial hierarchy that has dominated Canada’s wine market for decades.

Quebec’s long-standing dominance appears increasingly vulnerable. With consistently negative growth rates and declining per capita consumption, Quebec may lose its top position if current trends continue unabated. The province’s 34.94% market share could erode significantly, particularly if its distinctive wine culture begins to align more closely with national trends. While Quebec’s French heritage provides a strong cultural foundation for wine consumption, younger generations appear less committed to this tradition than their predecessors.

Ontario shows greater resilience amid the national downturn. With more moderate declines and occasional growth years even in the post-pandemic era, Ontario is positioned to potentially overtake Quebec in total consumption by 2030 if current trajectories continue. The province’s diverse population, strong urban centers, and robust retail system provide structural advantages that may buffer against broader negative trends.

British Columbia faces the most uncertain outlook among major wine provinces. Despite strong per capita consumption and a thriving local wine industry, BC has experienced the most volatile declines in recent years, suggesting potential structural issues in its wine market. The -27% drop in 2022 raises particular concerns about the province’s ability to maintain its market position. However, BC’s established wine tourism industry and domestic production capacity could provide recovery potential if properly leveraged.

Alberta’s consumption patterns appear closely tied to its resource-dependent economy. If energy prices and economic conditions improve, Alberta could see consumption stabilize or grow, potentially increasing its current 8.35% market share. However, the province’s privatized retail system creates unique market dynamics that may respond differently to changing consumer preferences.

Emerging regions show intriguing potential for increased market significance. Nova Scotia, with its growing wine industry centered in the Annapolis Valley, could see increased market share as local production drives consumption. Prince Edward Island’s strong per capita numbers (10.7 liters) indicate growth potential despite its small population base.

If current decline rates continue, Canada’s total wine consumption could fall below 450 million liters by 2030, returning to levels last seen around 2012-2013. However, this scenario assumes continuation of current trends without intervention, industry adaptation, or generational shifts in consumer preferences.

Several wild card factors could significantly alter these projections:

- Climate Change Impact: Warming temperatures could expand Canada’s domestic wine production capabilities, potentially stimulating local consumption through wine tourism and regional pride.

- Demographic Shifts: As younger Canadians develop their consumption patterns and purchasing power, their preferences will increasingly shape the market. If industry efforts to engage these consumers succeed, current decline trends could moderate.

- Economic Conditions: Wine consumption historically correlates with economic confidence and disposable income. Post-pandemic economic recovery patterns will influence consumption trajectories.

- Regulatory Changes: Any significant shifts in provincial alcohol regulation or distribution systems could dramatically alter consumption patterns. Privatization efforts, direct-to-consumer shipping laws, or tax structure changes would have outsized impacts.

- Health Perception Evolution: Consumer understanding of wine’s health implications continues to evolve. New research or changing health guidelines could either accelerate moderation trends or potentially reverse them.

The most likely scenario suggests a smaller but potentially more valuable Canadian wine market by 2030, with Ontario potentially overtaking Quebec as the country’s largest wine market both in volume and value terms. However, this transformed market will likely place greater emphasis on premium products, local production, and authentic experiences rather than mass consumption – potentially creating opportunities even within an overall contracting category.

What Does Your Province’s Wine Spending Say About Its Economy?

Wine consumption patterns across Canada’s provinces and territories offer a fascinating lens through which to examine broader economic structures, cultural values, and consumer priorities. The variations revealed in the data go far beyond simple preferences to illuminate fundamental aspects of regional economic identity.

Price sensitivity varies dramatically across provinces, revealing underlying economic confidence and discretionary spending patterns. Quebec’s high volume (164.45 million liters) but proportionally lower revenue ($2.79 billion) suggests greater price sensitivity among consumers who prioritize wine as part of daily life but seek value. This aligns with Quebec’s traditionally more egalitarian approach to luxury goods and slightly lower average household incomes compared to Ontario.

In contrast, Ontario’s premium spending behavior ($17.80 per liter average) indicates greater disposable income directed toward wine as a luxury or status good. This mirrors Ontario’s more stratified economy, with significant wealth concentration in the Greater Toronto Area driving premium consumption even as more rural regions may show different patterns.

British Columbia’s intriguing price-volume relationship ($13.32 per liter – significantly lower than other major provinces) suggests a democratized approach to wine, potentially driven by local production and a culture that integrates wine into everyday life rather than reserving it for special occasions. This reflects BC’s distinctive economic model that balances resource wealth, tourism, and lifestyle priorities differently than other major provinces.

Economic confidence strongly correlates with wine consumption trends across all provinces. The post-2019 national decline coincides with increased economic uncertainty, first from the pandemic and later from inflation and rising interest rates. This suggests wine consumption serves as a sensitive barometer for discretionary spending confidence among middle and upper-middle-class Canadians.

Regional economic structures are clearly reflected in consumption volatility. Resource-dependent provinces like Alberta show more volatile consumption patterns that appear to track with energy price fluctuations. The province’s wine consumption curve shows noticeable correlation with oil price cycles, suggesting disposable income in Alberta’s economy remains closely tied to resource extraction prosperity despite diversification efforts.

Cultural factors clearly transcend economics in specific regions. Quebec maintains high per-capita consumption (22.3 liters) despite various economic conditions, suggesting cultural factors play a stronger role than in other provinces. Similarly, Yukon’s surprisingly strong per capita consumption (13.3 liters) likely reflects both its unique demographic profile and distinctive northern lifestyle patterns rather than purely economic factors.

Geographic isolation impacts pricing and consumption in revealing ways. Northern territories show lower consumption but higher per-unit prices, reflecting logistical challenges in supply chains. This price premium serves as a proxy for the “northern premium” paid across consumer goods categories in remote regions, highlighting the economic realities of Canada’s geographic extremes.

The provincial data also reveals interesting urban-rural divides within provinces. While provincial averages provide a useful overview, consumption and spending patterns likely vary significantly between major urban centers and rural areas within each province, reflecting Canada’s increasingly divergent urban-rural economic development patterns.

The Canadian wine market’s recent contraction in the face of broader economic growth until recent headwinds suggests specific pressures on middle-class discretionary spending. While GDP growth remained positive through most of this period, wine’s decline points to possible compression of middle-class luxury spending – a concerning economic indicator beyond the beverage category itself.

These provincial wine consumption patterns tell a complex story about Canada’s economic and cultural landscape that transcends simple beverage preferences. From Quebec’s culturally-rooted but price-conscious consumption to Ontario’s premium-focused approach, from BC’s localized wine economy to Alberta’s resource-linked fluctuations, each province’s relationship with wine reflects its broader economic identity and priorities in revealing ways.

- How Much Beer Are Canadians Drinking in 2025?

- How Much Cider Are Canadians Drinking in 2025?

- How Much Spirit Are Canadians Drinking in 2025?

- How Much Alcohol Are Canadians Drinking in 2025?

Sources

Statistics Canada. Table 10-10-0010-01 Sales of alcoholic beverages types by liquor authorities and other retail outlets, by value, volume, and absolute volume